Pliny's fortune

This section offers some insights on the impact that this work had and still continues to have on different societies and times.

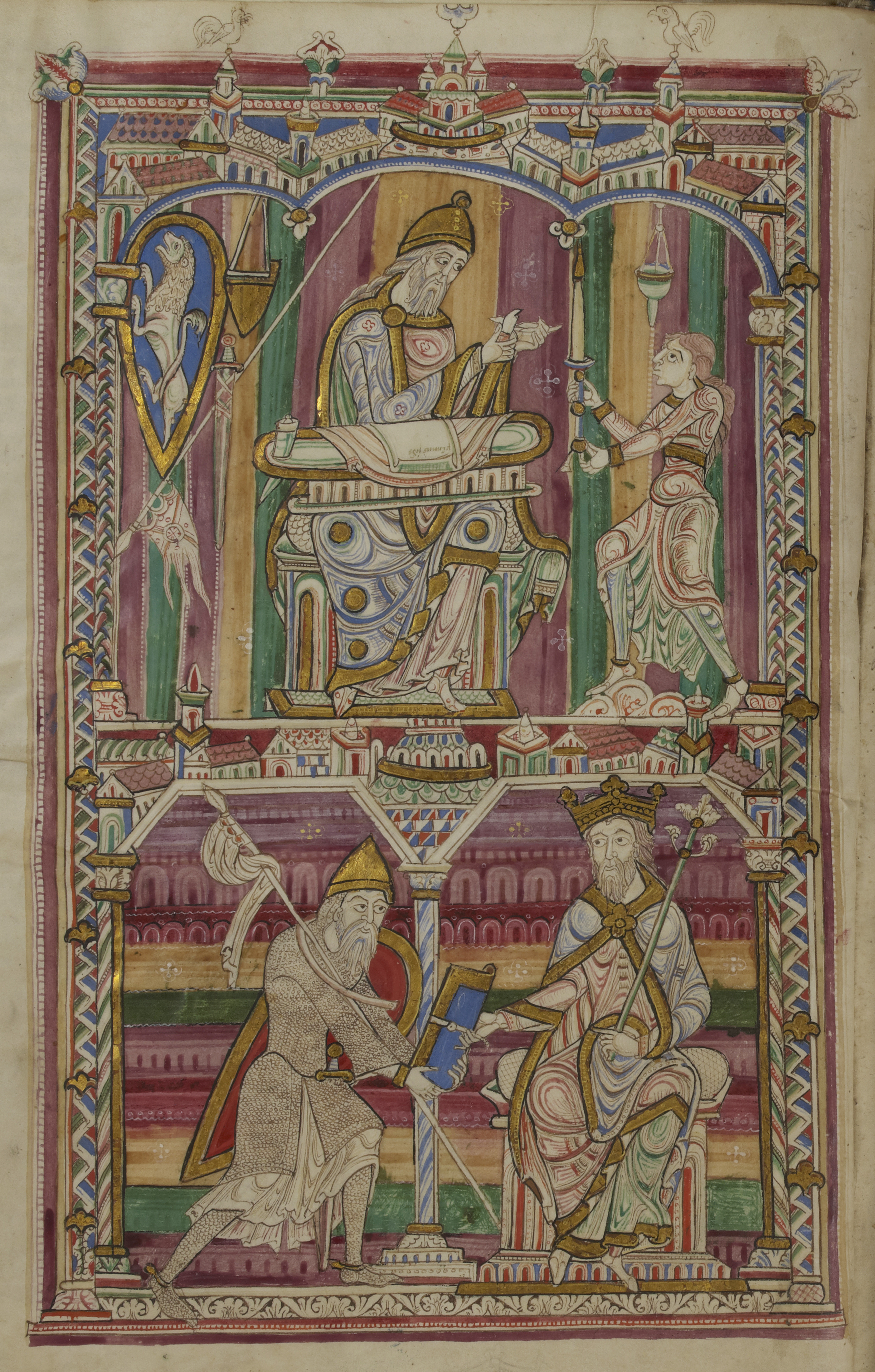

Manuscipt of the “Naturalis Historia” from St. Vincent Abbey in Le Mans, mid 12th century. Le Mans, Médiathèque Louis Aragon, ms. 263, f. 10v.

Parchment edition of Cristoforo Landino’s translation, 1478. Manchester, John Rylands University Library, incunabolo n. 3380.

La fortuna di Plinio dalla tarda antichità all’epoca moderna

Eliana Carrara – Nicoletta Marcelli

The paper here proposed aims to deal with the somewhat wide and articulated theme of the reception of the Naturalis Historia from late Antiquity to the Modern Era (to be precise, to the seventeenth century). Our intention, with no claim to exhaustiveness, is to offer in the pages that follow a kind of foothold, an Ariadne’s thread enabling us to follow the long and steep path starting from the first testimonies, in the fifth century AD, to this work by Pliny the Elder thence to proceed, through its transmission via the monastic scriptoria and the Carolingian Renaissance, to its diffusion by means of the press and hence to its affirmation in sixteenth century publishing. The textual history of the Naturalis Historia is thus interwoven with that of the many men of culture, both lay and religious, who have taken upon themselves the material preservation of the works in the various codices, copying them by hand on parchment and subsequently on paper, or who have attempted to correct errors and lacunae in the manuscripts of the testimonies so as to create a text as free from defects as possible.

The fortunes of the only surviving encyclopaedia of the ancient world owe much to all those men of letters who have quoted or synthesised it in their works or who have left behind explicative notes (or at times notes full of doubts, but just as precious to us in order to explain what they knew and what questions they asked themselves in the face of such a text) in the margins of the codices of the Naturalis Historia that they possessed or were able to consult: and the names of Francesco Petrarca and Poliziano are particularly significant in this regard. Just as important was the translation into the vernacular by Cristoforo Landino, who in the Florence of Lorenzo il Magnifico dedicated himself to the task of rendering the work legible also to those who were not too familiar with the Latin of Pliny’s text.

The Naturalis Historia was thus rendered freely perusable by the artists, and confirmed by the latter not only as an extraordinary repositorium of information regarding the arts, artists and techniques of the past and as a testing ground for measuring their own creative capacities (in a strict comparison between Ancients and Moderns); it also became the privileged witness to the social worth of the artist himself thanks to the comparison with renowned examples from the Classical world: we only need mention the name of Apelles and his relationship with Alexander the Great. Quoted, copied and translated, Pliny’s work was also the subject of a numerous series of iconographic derivations, with depictions inspired by the vicissitudes of the most famous artists or by ancient works that have been inexorably lost but which were celebrated by the Roman writer; its reliability was proved beyond a doubt by the discovery of the Laocoön group in Rome in 1506, handed down to us by numerous testimonies of the time.

> CONTINUE