PROTOGENES’ IALYSUS.

Reconstructing the biography of a lost masterpiece.

Eva Falaschi

Published: June 2020

If you are interested in reading the complete contribution, see E. Falaschi, More than words. Restaging Protogenes’ Ialysus. The many Lives of an Artwork between Greece and Rome. In G. Adornato – I. Bald Romano – G. Cirucci – A. Poggio (eds.), Restaging Greek Artworks in Roman Times, 173-190. Milano: LED, 2018 (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.

Knowing the Ialysus: an introduction

The fame – In book 35 of Naturalis Historia Pliny the Elder celebrates the Ialysus as Protogenes of Caunus’ best painting (35.102 Palmam habet tabularum eius [scil. Protogenes’] Ialysus) and, in general, as a masterpiece of Greek art. Pliny’s praise is not isolated in ancient times, as many other authors also exalted the greatness of the Ialysus. Strabo (14.2.5), for example, considers it one of the votive offerings worth being seen in Rhodes, after the Colossus of Helius, and Cicero mentions it aside other great works by Apelles, Polykleitos and Pheidias as one of the best examples of Greek art (Cic. Orat. 2.5 and 2.8; Att. 2.21.4; Verr. 2.4.135). Plutarch, instead, describes Demetrios Poliorketes’ and Apelles’ admiration of this painting (Demetr. 22.4-7).

The subject – Despite its great fame, the Ialysus went lost and the only information on it comes from

literary sources. Unfortunately, we know almost nothing about the subject. It represented the Rhodian eponymous hero Ialysus, but no myth on him is transmitted. Thanks to Pliny the Elder (NH 35.102), we learn about the presence of a panting dog (anhelantis). On these bases different reconstructions of the painting have been proposed: Ialysus as a hunter has been the major interpretation, but other scholars have suggested Ialysus killed by his furious dog. It has also been hypothesized that the paintings of other two Rhodian local heroes made by Protogenes, Cydippe and Tlepolemus, should be linked to the Ialysus and constitute a cycle with it.

The method – Protogenes’ Ialysus can be declared a masterpiece irremediably lost, because of not just the loss of the canvas, but also the impossibility of imagining even what it represented. Nonetheless, later literary sources are prodigal in giving information on this painting, its creation, its history, and its vicissitude. Thanks to these pieces of news, we still have the chance to reconstruct its “biography” through time and trace its long history at least from the 4th century BC to the Byzantine times, first in Greece and later in Rome. At the same time, we are also able to understand the values and meanings this painting assumed in different periods and places, and the impact it had on its viewers.

This result can be achieved by reading literary sources in a chronological perspective and analyzing them in the context they were conceived and transmitted, never neglecting the author who gives the piece of news. In an art historical perspective, the importance of this approach lies in the possibility of recovering much information – otherwise lost – on the reception of an artwork in later times, and tracing at the same time its history. In so doing, it is possible to shift from a conception where artworks are fixed masterpieces created by an artist in a precise year, to the idea that artworks are alive objects which can be moved from one place to another and change meaning, functions, values through time.

1. The Greek life: the Ialysus in Rhodes

The praise – The Ialysus was celebrated in Rhodes for long as a great artwork. The fact that it was considered among the finest of all time was probably in no small part down to the judgement of Apelles. According to Plutarch, while admiring the painting, Apelles was so moved that he lost his voice, but later he said that “great was the toil and astonishing the work”, even though it did not have the χάρις his own works had (Demetr. 22.6). Apelles was considered the best painter of the ancient times. According to Pliny the Elder, he contributed to art not only the creation of art masterpieces, but also the development of new artistic theories and technique, which were discussed in his book on painting. Probably, in this book he also celebrated the Ialysus as a great artwork (NH 35.79-80).

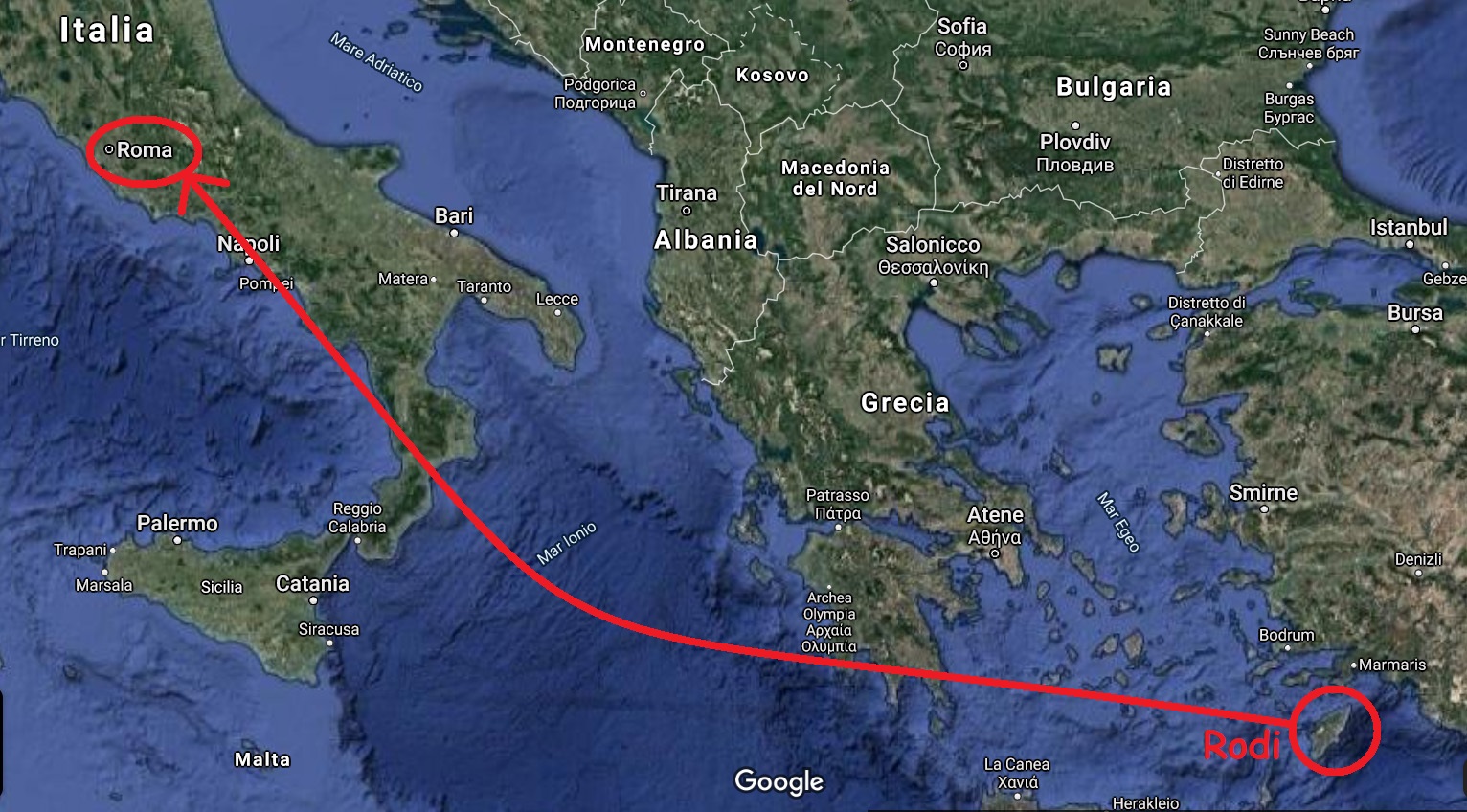

The siege of Rhodes – This undisputed fame saved the Ialysus in a great moment of crisis for Rhodes. Because of his strategic position in the Mediterranean Sea, the island played an important role in the political and economic theater of the Hellenistic kingdoms. A very crucial event in the history of Rhodes was Demetrios Poliorketes’ siege in 305/4 BC. In that occasion, in front of the Rhodians’ request for saving the Ialysus, Demetrios, because of his admiration of the painting, did not hesitate to spare it. According to Plutarch, he replayed the Rhodians that he would have preferred burning down his father’s portraits than such a work of great toil and art (Demetr. 22.5). Pliny (NH 35.104) and Gellius (NA 15.35), instead, state that he even gave up conquering the island in order to save the Ialysus.

Last traces in Rhodes – After Demetrios’ siege of Rhodes, we lose track of the Ialysus for some centuries. Nonetheless, we learn that at the times of Cicero and Strabo it was still in Rhodes: the two authors consider it an unmissable masterpiece for people who visited the island, at the same level of the Colossus of Helius and the masterpieces by Apelles, Polykleitos and Pheidias.

2. The Roman life: the Ialysus in Rome

A glorious past – Before arriving in Rome, the Ialysus had already had a long history. What arrived in the Urbs was not just a great masterpiece of art, but an artwork with a glorious past, which was still renowned. In this perspective, it appears helpful to investigate what was still known about this past history in the Imperial Age, in order to understand how this set of news influenced the restaging of the Ialysus in Rome. At the same time, this analysis allows to highlight which new meanings (aesthetic, political, social) the Ialysus assumed in this new context and which ancient values it continued to embody. Finally, the paper takes into consideration if the restaging of the Ialysus in Rome impacted the way Imperial authors narrate its “Greek life”.

Demetrios’ admiration – In the Imperial Age the Ialysus was especially famous because Demetrios Poliorketes, during his siege of Rhodes in 305/4 BC, decided to spare it. The episode is recalled and narrated in details by various ancient sources, and this confirms its fame. Pliny (NH 7.126 and 35.104-105), Plutarch (Demetr. 22.4-5) and Gellius (NA 15.31) refer slightly different version of the episode, but all of them celebrate Demetrios’ fondness for art. This indicates that the appreciation of the Ialysus entered the ancient discussion about Demetrios and became one of the elements to define his controversial personality.

A great labour of art – Even though Plutarch’s focus is the siege of Rhodes, he decides to offer the reader a digression on the Ialysus, in order to celebrate this great artwork. In fact, to justify Demetrios’ definition of the Ialysus as a great labour of art (τέχνης πόνον τοσοῦτον), he adds that it took Protogenes seven years to complete the painting and refers Apelles’ praise of the Ialysus. These pieces of information are confirmed by other contemporary authors. According to Pliny, Apelles admired Protogenes’ painting which betrayed great toil and the most anxious industry (NH 35.80 opus inmensi laboris ac curae supra modum anxiae). Moreover, if Plutarch speaks about seven years, Marcus Cornelius Fronto, in a letter to Domitilla Lucilla dated to 143 AD, increases them to eleven and introduces Protogenes as an ethical example of devotion to work. Fronto intends to apologise to Domitia for not writing to her earlier, because he was busy composing an oration for her son: when he is absorbed, nothing can dissuade him from work, just like Protogenes, who needed eleven years to end the Ialysus and for eleven years painted only that artwork (Ep. 2.3.4). In conclusion, in the Imperial age the Ialysus was especially famous because it took a long time to be painted and this justified, for example in Plutarch’s view, its artistic greatness. This fame which followed the painting and its creation was then elaborated in different way till to becoming the symbol of Protogenes’ devotion to work, as it appears in Fronto.

Apelles’ praise – Apelles’ celebration of the Ialysus was well-known in the Imperial Age. It was probably contained in his writing on painting and was considered a proof of the greatness of the Ialysus. If the best painter of the past expressed this opinion on the Ialysus, every person interested in art and aware of that judgment had to consider it an unmissable masterpiece during a tour of Rome. In this sense Apelles’ judgment probably influenced the reception of the painting in Rome – and, before that, probably also in Rhodes – and maybe even its transfer to the Urbs. In some way, also Plutarch attributes to Apelles’ judgment precisely this value, because he uses it to support and justify Demetrios’ extreme admiration of the painting. In other words, it seems that at least in the Imperial time Apelles became the guarantor of the greatness of the Ialysus.

Technical aspects & anecdotes – Pliny relates some anecdotes about the execution of the Ialysus: Protogenes ate just soaked lupins to spare time, so that he did not have to drink; he used four layers of color to avoid the damages of time, and he painted more than once the foam on the mouth of the dog, because he was not satisfied with it (NH 35.102-104). Pliny does not provide just anecdotes, but moves to a more technical level and celebrates Protogenes’ diligentia. First of all, all the anecdotes refer to the realization of the Ialysus: we are, in other words, in Protogenes’ workshop. Moreover, the story of the soaked lupins expresses Protogenes’ dedication to painting, while at the basis of the other two anecdotes there is a technical problem Protogenes had to face: the four layers of colors are the painter’s solution to making the painting enduring (contra obsidia iniuriae et vetustatis); the anecdote of the sponge, instead, deals with the exhausting search for veritas (cum in pictura verum esse, non verisimile vellet) and the necessity of veiling artificiality (displicebat autem ars ipsa). We can conclude that in the Imperial Age an art historical tradition about the way Protogenes made his paintings, in particular the Ialysus, was still known: cura, diligentia, slowness, search for veritas were the main features of his art and they could be still appreciated in the Ialysus, which was the result of that conception of art and also its emblem. On the other side, these technical features had been developed in a more ethical direction, so that Protogenes had become the symbol of devotion to work and the Ialysus the most perfect product of that devotion, as it can be seen in Fronto.

The importance of the dog – In Pliny’s account a lot of attention is put on the anecdote of the sponge: Protogenes was not satisfied with the depiction of the foam around its mouth and tried more than once to make it, until he threw a sponge against the canvas and got by chance the perfect result he could not reach with all his art (NH 35.102). Since this story is not connected with the main character of the painting, Ialysus, it seems to suggest a change of value in the importance given to the figures in the painting. When the painting was in Rhodes and was a votive offering, Ialysus was the main subject, the reason why the painting was commissioned. But later the attention probably shifted from the Ialysus to the dog, which was the best figure in the painting (canis mire factus) and whose realization was renowned because of the trick of the sponge. It is probable that in Rome, once the religious connection of Ialysus with Rhodes had been lost, people went to see the painting in order to admire, above all, the famous dog. This could also explain why our sources do not describe the figure of Ialysus, but refer just to the dog.

A philosophical reflection – Pliny interprets Protogenes’ anecdote of the sponge as an example of how the Chance manages to imitate nature, while art fails. This concept is expressed through two sentences (fecitque in pictura fortuna naturam and ita Protogenes monstravit et fortunam) which are not a real part of the narration but rather external commentaries to it. Only Pliny understands Protogenes’ Ialysus in this light, but this interpretation is well attested in philosophy and rhetoric (e.g. Plut. De fortuna 99a-c) for a similar anecdote related to Apelles. This latter was not satisfied with the foam on the mouth of a horse and, in anger, threw a sponge against the canvas. Therefore, Pliny testifies that Protogenes’ Ialysus could also offer to a well-educated viewer, who learned philosophy and rhetoric at school, a philosophical reflection about the Chance and the limits of human techne.

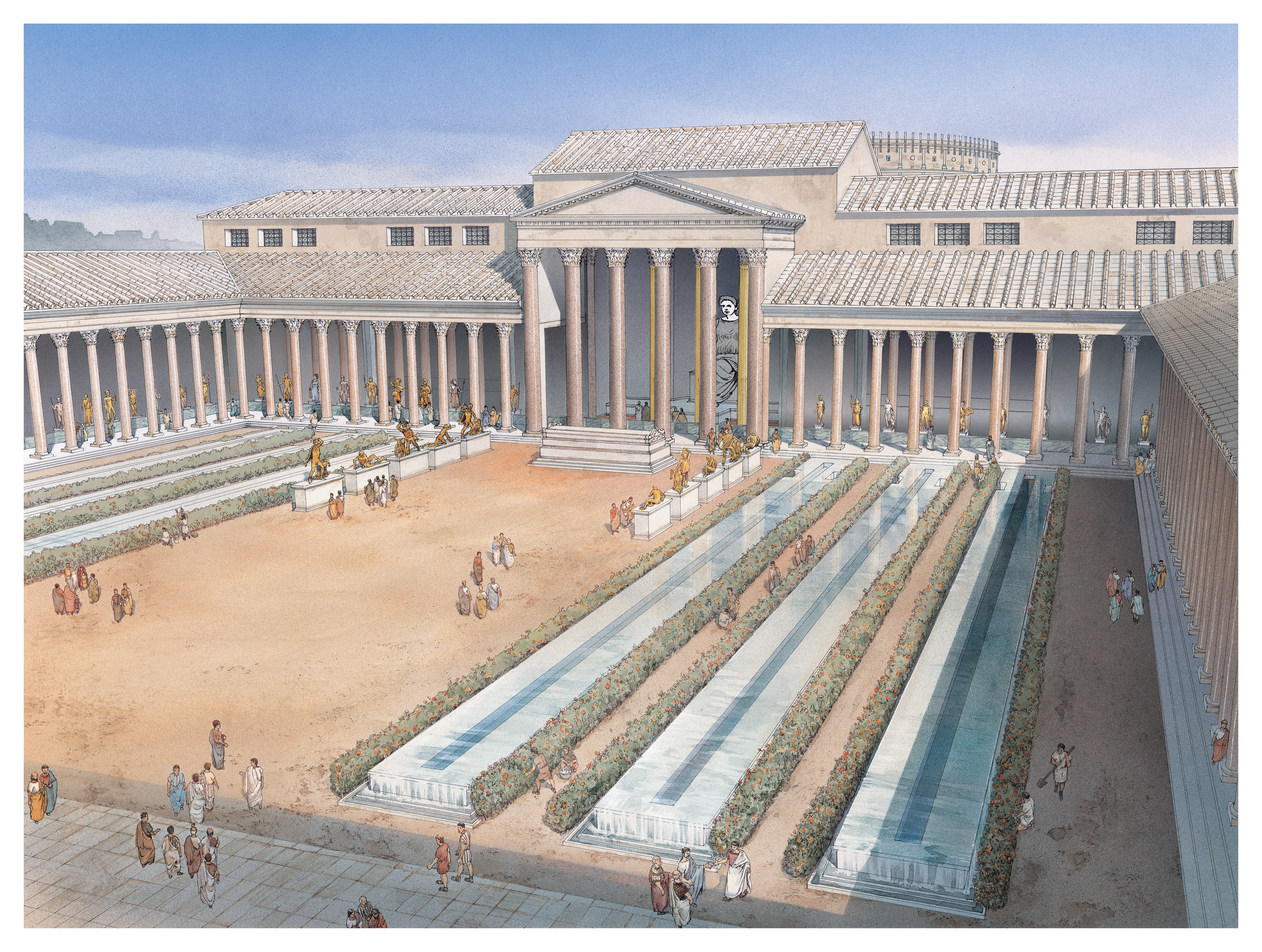

The Ialysus in Rome: its impact – Pliny the Elder, Plutarch, Fronto, Gellius were well educated members of the elite class, collectors of artworks, erudites, readers of art historical treatises. Some of them (or maybe all) could also admire with their eyes the Ialysus in Rome, but surely they all knew its great fame. At this point, we could wonder if and how the presence of the Ialysus in Rome affected the accounts of our sources. It is possible that the chance to see the painting pushed different intellectuals to mention it in their works. It is with a bit of pride, for example, that Pliny says that the greatest work of Protogenes was in the Templum Pacis. This is the first information he gives about the painting, and we cannot exclude that the possibility of seeing the Ialysus in Rome encouraged him to offer the reader so many pieces of information about it. In fact, just a few artworks receive so much attention in the Naturalis Historia. In Plutarch’s account, instead, regret is expressed for the loss of the painting in Rome: since, as shown below, we cannot define who expressed this regret, it is difficult to say which role the restaging of the painting in Rome plays exactly in this sentence. It is not clear, for example, if there is a veiled reference to the stealing of the painting from Greece, but there is no way to exclude it.

3. Epilogue. The end of the Ialysus

Which fire? – The reconstruction of these events is very problematic. In fact, we have just a few clues to establish the date of this fire: it should be before Plutarch’s death, around AD 120, and before the composition of the Life of Demetrius, which according to the scholars was probably composed in the second decade of the 2nd century AD. On these chronological bases, Plutarch’s statement disagrees with our historical data on the Templum Pacis: in fact, we learn from contemporary literary sources and from archaeological data that it was destroyed under the reign of Commodus, in AD 192, and then restored in the Severan Times. Other catastrophic events which involved the Templum Pacis are known just for later times.

Plutarch’s statement – Therefore, in order to correctly comprehend the data in our possession and resolve this inconsinstency, it is, first of all, crucial to reconsider Plutarch’s statement. It is not clear if the place he refers to is the Templum Pacis. In fact, he does not say it explicitly, but this conclusion is usually gathered by crossing Plutarch’s account with the information given by Pliny about the location of the Ialysus in the Templum Pacis. Moreover, in Plutarch’s account it is not completely plain if the place of collection of the artworks is the same as the place of destruction, even though it seems more probable that it is. Indeed, Plutarch’s description fits very well for the Templum Pacis, which was very famous as a collecting place of great artworks (Joseph. BJ 7.158-160). Therefore, it is possible that Plutarch refers indeed to the Templum Pacis, but it cannot be sure, because it was not the only place were famous Greek artworks were collected in Rome.

The hypothetical scenarios – Starting from these observations, it is possible to express different hypotheses about the destiny of the Ialysus in Rome.

- The Ialysus remained in the Templum Pacis until its destruction. It implies, first of all, that in his account Plutarch refers to the Templum Pacis. Afterwards, we could reconstruct the events in two ways:

- The Ialysus was destroyed by a fire, maybe small in proportions, which arose in the Templum Pacis between Pliny’s and Plutarch’s statement and which is not recorded by our sources.

- The Ialysus was destroyed in the Templum Pacis during the fire of AD 192. In this case, we should conclude that the reference to the destruction of the Ialysus in the Life of Demetrius does not come from Plutarch, but it is a later addition, after AD 192. The sentence expresses regret because of the loss of the painting: it could be Plutarch’s regret for the loss of an extraordinary artwork which had been stolen from Greece, but it could also be the bitter reflection of a later reader prompted by Plutarch’s celebration of the painting.

- The Ialysus was moved from the Templum Pacis, where Pliny saw it, to another place, where it was destroyed, and Plutarch refers to this second place as the place of destruction.

The Afterlife – Despite the numerous difficulties, we can conclude that the Ialysus went lost probably at some point between the first and the 2nd century AD in Rome. Nonetheless, its history went on and after its destruction it continued providing inspiration for later authors. In fact, Ialysus’s fame did not diminish even after its loss. Well educated and erudite people like Pomponius Porphyrion (Comm. Hor. Ars 323-324, 3rd century AD) continued to consider it one of the best Greek artworks ever existed and proposed its beauty and greatness as an emblem of devotion to work. In this perspective, it is not surprising that after its destruction, when Protogenes’ diligentia and artistic greatness could not be appreciated in the Ialysus anymore, the painting offered mainly an ethical example.

The fame of the Ialysus arrived up to Byzantium. In fact, in the 10th century AD it is probably mentioned by the Suda under the lemma dedicated to Protogenes. In this context it is still celebrated as a great artwork, very admired by Demetrios Poliorketes. After almost thirteen centuries the Ialysus was still a masterpiece worth being recorded and praised, even though it could not be admired anymore.

Index

Knowing the Ialysus: an introduction

§.1. The Greek life: the Ialysus in Rhodes

§.2. The Roman life: the Ialysus in Rome

§.3. Epilogue: the end of the Ialysus